Debugging¶

System Development with Python

- Maria McKinley

parody@uw.edu

Topics¶

- The call stack

- Exceptions

- Debugging

The Call Stack¶

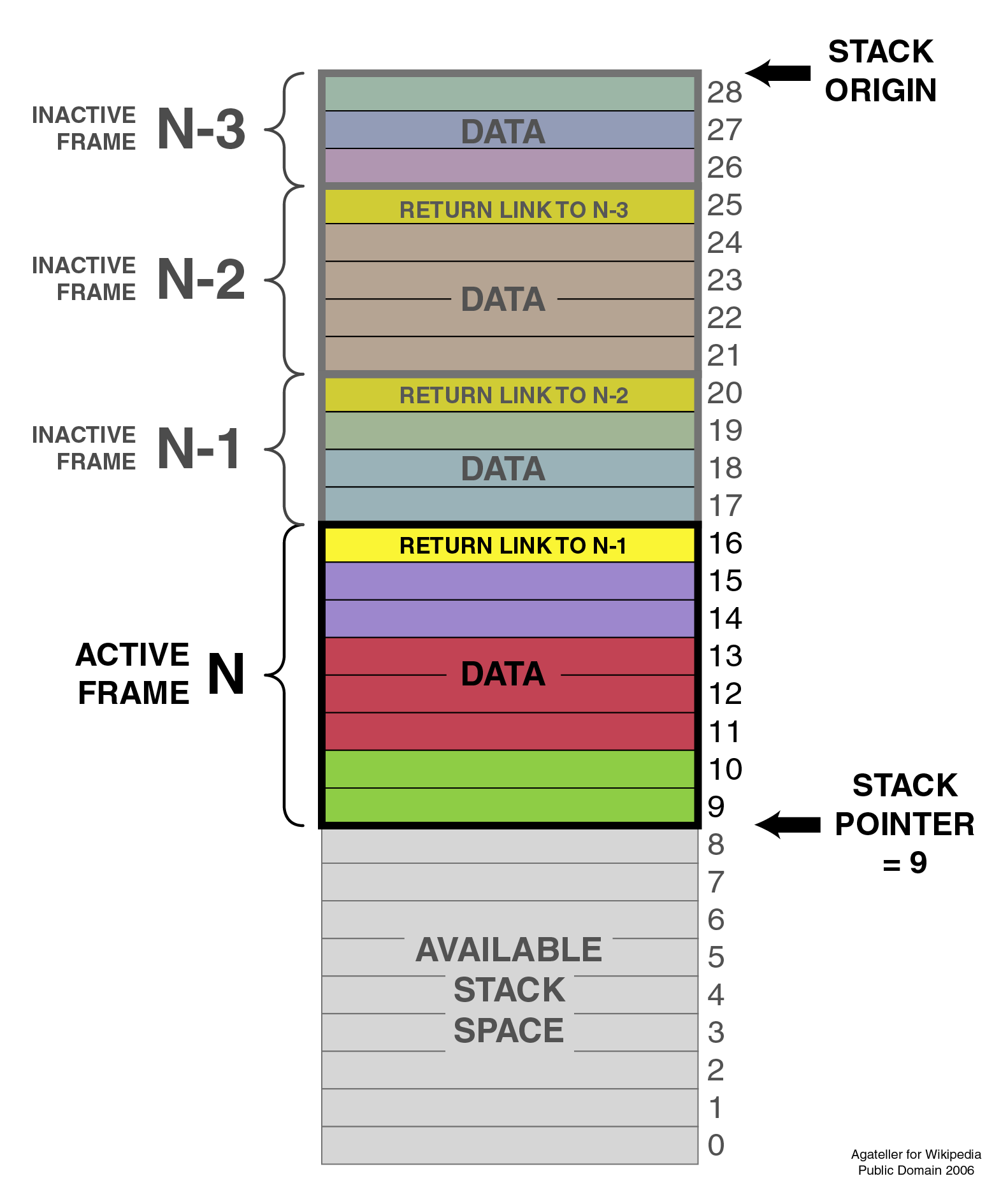

- A stack is a Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) data structure (stack of plates)

- The call stack is a stack data structure that stores information about the current active function calls

- The objects in the stack are known as “stack frames”. Each frame contains the arguments passed to the function, space for local variables, and the return address

- It is usually (unintuitively) displayed like an upside-down stack of plates, with most recent frame on the bottom.

- When a function is called, a stack frame is created for it and pushed onto the stack

- When a function returns, it is popped off the stack and control is passed to the next item in the stack. If the stack is empty, the program exits

Visualize the stack!¶

How deep can that stack be?

i = 0

def recurse():

global i

i += 1

print(i)

recurse()

recurse()

That value can be changed with sys.setrecursionlimit(N)

If we try to put more than sys.getrecursionlimit() frames on the stack, we get a RecursionError (derived from RuntimeError), which is python’s version of StackOverflow

import inspect

def recurse(limit):

local_variable = '.' * limit

print(limit, inspect.getargvalues(inspect.currentframe()))

if limit <= 0:

return

recurse(limit - 1)

return

recurse(3)

module https://docs.python.org/3/library/inspect.html

more on recursion http://www.mariakathryn.net/Blog/60

Exceptions¶

It’s easier to ask for forgiveness than permission (Grace Hopper)

When either the interpreter or your own code detects an error condition, an exception will be raised

The exception will bubble up the call stack until it is handled. If it’s not handled anywhere in the stack, the interpreter will exit the program.

At each level in the stack, a handler can either:

- let it bubble through (the default if no handler)

- swallow the exception (the default for a handler)

- catch the exception and raise it again

- catch the exception and raise a new one

Handling exceptions¶

The most basic form uses the builtins try and except

def temp_f_to_c(var):

try:

return(float(var) - 32)/1.8000

except ValueError as e:

print("The argument does not contain numbers\n", e)

A few more builtins for exception handling: finally, else, and raise¶

x = 5

y = "this"

try:

result = x / y

except (ZeroDivisionError, ValueError) as e:

print("caught division error or maybe a value error:\n", e)

except Exception as e: # only do this if absolutely necessary, or if planning to re-raise

errors = e.args

print("Error({0})".format(errors))

# or you can just print e

print("unhandled, unexpected exception:\n", e)

raise

else:

print("do this if there is code you want to run only if no exceptions, caught or not")

print("errors here will not be caught by above excepts")

finally:

print("this is executed no matter what")

print('this is only printed if there is no uncaught exception')

It is even possible to use a try block without the exception clause:

try:

5/0

finally:

print('did it work? why would you do this?')

Built-in exceptions

[name for name in dir(__builtin__) if "Error" in name]

If one of these meets your needs, by all means use it. You can add messages:

raise SyntaxError("That was a mispelling")

If no builtin exceptions work, define a new exception type by subclassing Exception.

class MyException(Exception):

pass

raise MyException("An exception doesn't always prove the rule!")

It is possible, but discouraged to catch all exceptions.

try:

my_cool_code()

except:

print('no idea what the exceptions is, but I caught it')

An exception to this exception rule is when you are running a service that should not ever crash, like a web server. In this case, it is extremely important to have very good logging so that you have reports of exactly what happened and what exception would have been thrown.

Further reading

Debugging¶

Python Debugging

- You will spend most of your time as a developer debugging.

- You will spend more time than you expect on google.

- Small, tested functions are easier to debug.

- Find a bug, make a test, so it doesn’t come back

Tools¶

- interpreter hints

- print()

- logging

- assert()

- tests

- debuggers

The Stack Trace¶

You already know what it looks like. Simple traceback:

maria$ python3 define.py python

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "define.py", line 15, in <module>

definition = Definitions.article(title)

File "/Users/maria/python/300/Py300/Examples/debugging/wikidef/definitions.py", line 7, in article

return Wikipedia.article(title)

File "/Users/maria/python/300/Py300/Examples/debugging/wikidef/api.py", line 26, in article

contents = json_response['parse']['text']['*']

TypeError: 'method' object is not subscriptable

But things can quickly get complicated. You may have already run into stacktraces that go on for a 50 lines or more.

Some helpful hints with stacktraces:¶

- May seem obvious, but… Read it carefully!

- What is the error? Try reading it aloud.

- The first place to look is the bottom.

- Trace will show the line number and file of exception/calling functions.

- More than likely the error is in your code, not established packages - look at lines in your code mentioned in the stacktrace first - Sometimes that error was triggered by something else, and you need to look higher. (probably more than one file in the stacktrace is your code)

If that fails you…

- Make sure the code you think is executing is really executing.

- Simplify your code (smallest code that causes bug).

- Debugger

- Save (and print) intermediate results from long expressions

- Try out bits of code at the command line

If all else fails…

Write out an email that describes the problem:

- include the stacktrace

- include steps you have taken to find the bug

- inlude the relative function of your code

Often after writing out this email, you will realize what you forgot to check, and more often than not, this will happen just after you hit send. Good places to send these emails are other people on same project and mailing list for software package. For the purpose of this class, of course, copy it into slack or the class email list.

Print¶

- print(“my_module.py: my_variable: “, my_variable)

- can use print statements to make sure you are editing a file in the stack

Console Debuggers¶

- pdb/ipdb

GUI debuggers (more about these below)¶

- Winpdb

- IDEs: Eclipse, Wing IDE, PyCharm, Visual Studio Code

help from the interpreter

- investigate import issues with -v:

python -v myscript.py

Verbose (trace import statements)

- inspect environment after running script with -i

python -i myscript.py

Forces interpreter to remain active, and still in scope

Useful tools from interpreter:¶

- In IPython, ‘who’ will list all currently defined variables

- locals()

- globals()

- dir()

Pros:

- You have it already, ships with the standard library

- Easy remote debugging (since it is non-graphical, see remote-pdb for true remote debugging)

- Works with any development environment

Cons:

- Steep-ish learning curve

- Easy to get lost in a deep stack

- Watching variables isn’t hard, but non-trivial

The 4-fold ways of invoking pdb¶

- Postmortem mode

- Run mode

- Script mode

- Trace mode

Note: in most cases where you see the word ‘pdb’ in the examples, you can replace it with ‘ipdb’. ipdb is the ipython enhanced version of pdb which is mostly compatible, and generally easier to work with. But it doesn’t ship with Python.

Postmortem mode

For analyzing crashes due to uncaught exceptions

python -i script.py

import pdb; pdb.pm()

More info on using Postmortem mode:

http://www.almarklein.org/pm-debugging.html

Run mode

pdb.run('some.expression()')

Script mode

python -m pdb script.py

“-m [module]” finds [module] in sys.path and executes it as a script

Trace mode

Insert the following line into your code where you want execution to halt:

import pdb; pdb.set_trace()

It’s not always OK/possible to modify your code in order to debug it, but this is often the quickest way to begin inspecting state

pdb in ipython

In [2]: pdb

Automatic pdb calling has been turned ON

%run app.py

# now halts execution on uncaught exception

If you forget to turn on pdb, the magic command %debug will activate the

debugger (in ‘post-mortem mode’).

The goal of each of the preceding techniques was to get to the pdb prompt and get to work inspecting state. Most commands can be short-cutted to the first letter.

% python -m pdb define.py

pdb> args # print arguments and values to current function

pdb> pp a_variable # pretty-print a_variable

pdb> where # print stack trace, bottom is most recent command

pdb> list # list the code including and surrounding the current running code

To repeat the current command, press only the Enter key

# execute until current function returns

pdb> return

# Execute the current line, stop at the first possible occasion

pdb> step

# Continue execution until the next line in the current function is reached or it returns.

pdb> next

# Continue execution until the line with a number greater than the current one is reached

or until the current frame returns. Good for exiting loops.

pdb> until

# move one level up the stack

pdb> up

# move one level down the stack

pdb> down

pdb> continue # goes until next breakpoint or end of program

# advanced: create commands to be executed on a breakpoint

pdb> commands

Breakpoints

pdb> help break

b(reak) ([file:]lineno | function) [, condition]

With a line number argument, set a break there in the current

file. With a function name, set a break at first executable line

of that function. Without argument, list all breaks. If a second

argument is present, it is a string specifying an expression

which must evaluate to true before the breakpoint is honored.

The line number may be prefixed with a filename and a colon,

to specify a breakpoint in another file (probably one that

hasn't been loaded yet). The file is searched for on sys.path;

the .py suffix may be omitted.

Can use up, down, where and list to evalutate where you are, and use that to set a new breakpoint in code coming up. Useful for getting out of rabbit holes.

pdb> break api.py:21 # set a breakpoint file:line #

pdb> break # list breakpoints

pdb> clear 1 # get rid of first breakpoint

pdb> break 35 # set a breakpoint in current file at line 35

# print lines in range

pdb> list 1,28

You can also delete(clear), disable and enable breakpoints

clear [bpnumber [bpnumber...]]

disable [bpnumber [bpnumber...]]

enable [bpnumber [bpnumber...]]

Conditional Breakpoints

pdb> break 9, j>3

Breakpoint 1 at .../pdb_break.py:9

pdb> break

Num Type Disp Enb Where

1 breakpoint keep yes at .../pdb_break.py:9

stop only if j>3

Condition can be used to add a conditional to an existing breakpoint

Invoking pdb with pytest

pytest allows one to drop into the PDB prompt via a command line option:

pytest --pdb

This will invoke the Python debugger on every failure. Often you might only want to do this for the first failing test to understand a certain failure situation:

pytest -x --pdb # drop to PDB on first failure, then end test session

pytest --pdb --maxfail=3 # drop to PDB for first three failures

Try some debugging! Here is a fun tutorial intro to pdb that someone created:

Python IDEs¶

PyCharm

From JetBrains, — integrates some of their vast array of development tools

Free Community Edition (CE) is available

Good visual debugging support

Eclipse

A multi-language IDE

Python support via http://pydev.org/

Automatic variable and expression watching

Supports a lot of debugging features like conditional breakpoints, provided you look in the right places!

Further reading

http://pydev.org/manual_adv_debugger.html

Visual Studio Code

Visual Studio Code has support for Python

(not the same as the monstrosity that is Visual Studio)

https://code.visualstudio.com/

winpdb

A multi platform Python debugger with threading support

Easier to start up and get debugging:

winpdb your_app.py