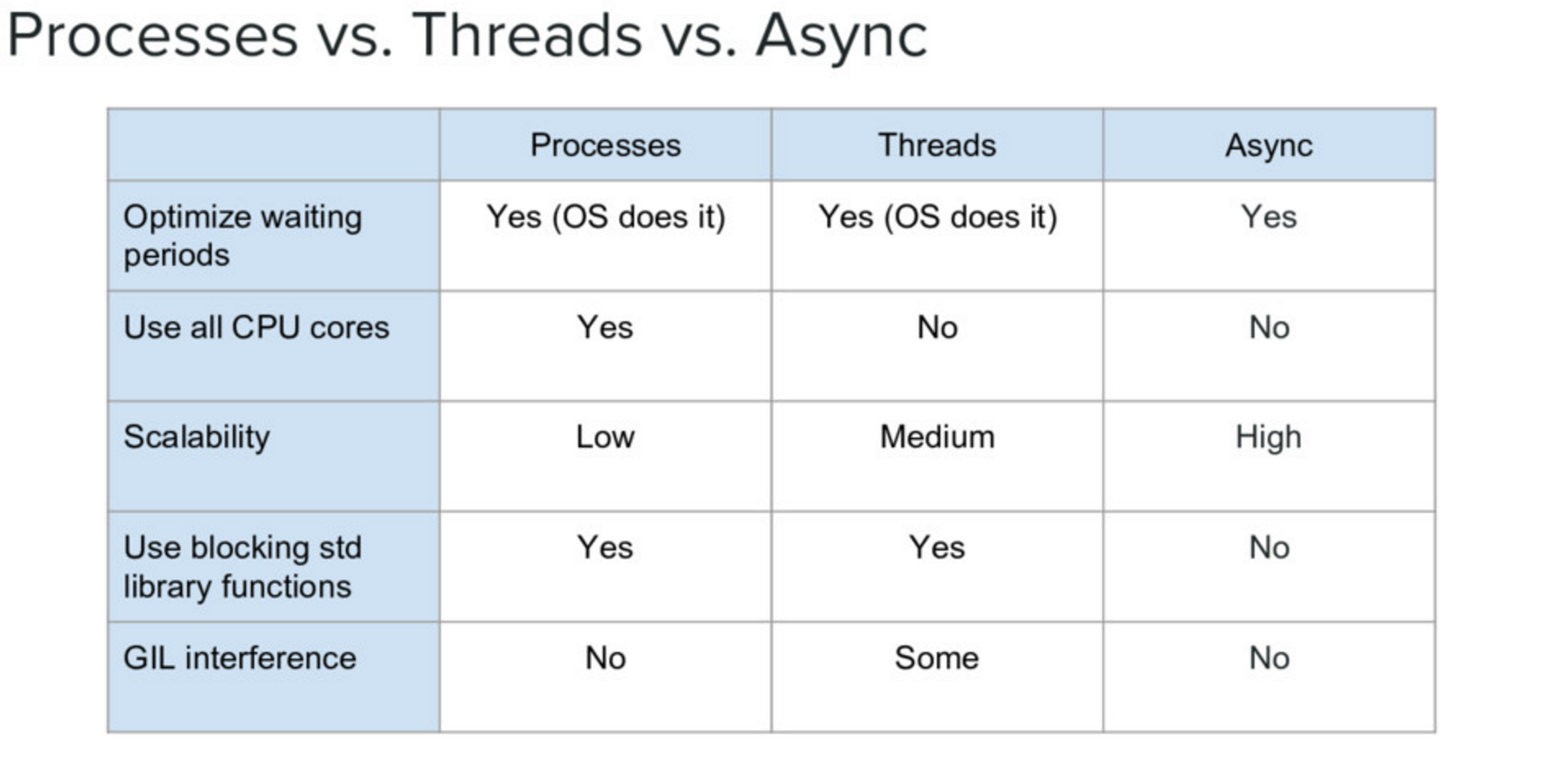

Concurrency Part 3: GIL¶

Global Interpreter Lock

(GIL)

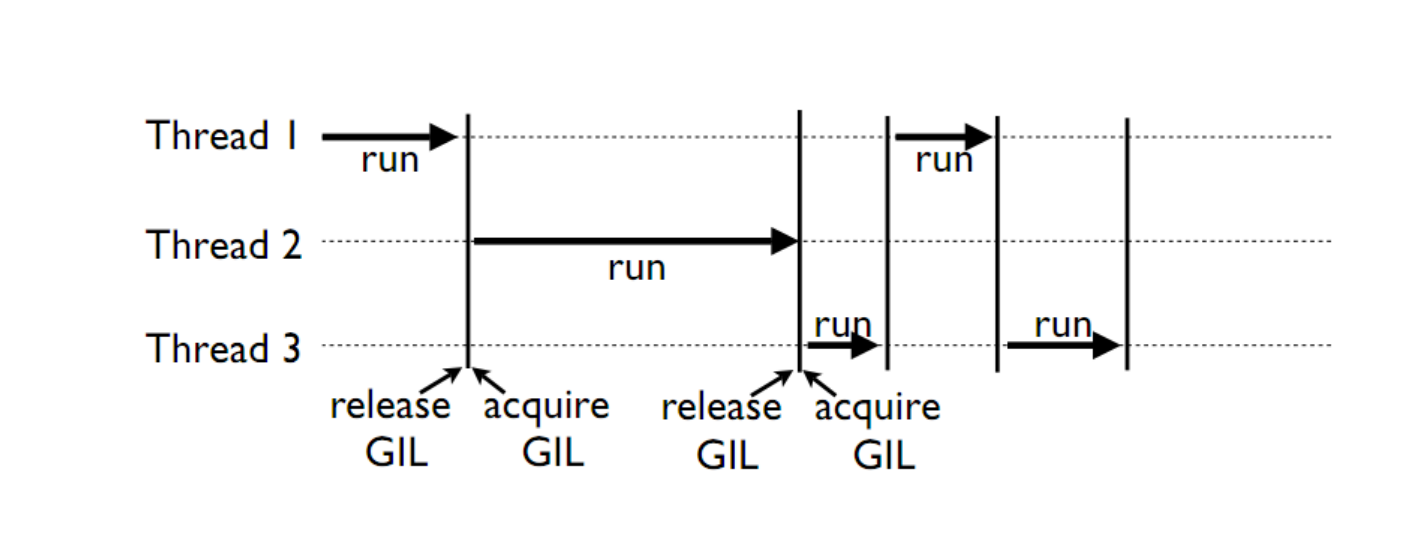

This is a lock which must be obtained by each thread before it can execute, ensuring thread safety

The GIL is released during IO operations, so threads which spend time waiting on network or disk access can enjoy performance gains

The GIL is not unlike multitasking in humans, some things can truly be done in parallel, others have to be done by time slicing.

Note that potentially blocking or long-running operations, such as I/O, image processing, and NumPy number crunching, happen outside the GIL. Therefore it is only in multithreaded programs that spend a lot of time inside the GIL, interpreting CPython bytecode, that the GIL becomes a bottleneck. But: it can still cause performance degradation.

Not only will threads not help cpu-bound problems, they can actually make things worse, especially on multi-core machines!

Python threads do not work well for computationally intensive work.

Python threads work well if the threads are spending time waiting for something:

Database Access.

Network Access.

File I/O.

Some alternative Python implementations such as Jython and IronPython have no GIL.

cPython and PyPy have one.

More about the gil

More on the GIL:

https://emptysqua.re/blog/grok-the-gil-fast-thread-safe-python/

If you really want to understand the GIL – and get blown away – watch this one:

http://pyvideo.org/pycon-us-2010/pycon-2010–understanding-the-python-gil—82.html

NOTE: The GIL seems like such an obvious limitation that you have to wonder why it’s there. Indeed, there have been multiple efforts to remove it. But it turns out that Python’s design makes that very hard (maybe even impossible) without severely reducing performance on single threaded programs.

The current “Best” effort is Larry Hastings’ gilectomy

But that may be stalled out at this point, too. No one should count on it going away in cPython.

Posted without comment¶

Advantages / Disadvantages of Processes¶

Processes are heavier weight – each process makes a copy of the entire interpreter (mostly…) – uses more resources.

You need to copy the data you need back and forth between processes.

Slower to start, slower to use, more memory.

But as the entire python process is copied, each subprocess is working with the different objects – they can’t step on each other. So there is:

no GIL

Multiprocessing is suitable for computationally intensive work.

Works best for “large” problems with not much data to pass back and forth, as that’s what’s expensive.

Note that there are ways to share memory between processes, if you have a lot of read-only data that needs to be used. (see Memory Maps)

Synchronization options:

Locks (Mutex: mutual exclusion, Rlock: reentrant lock).

Semaphore.

BoundedSemaphore.

Event.

Condition.

Queues.

Mutex locks (threading.Lock)¶

Probably most common.

Only one thread can modify shared data at any given time.

Thread determines when unlocked.

Must put lock/unlock around critical code in ALL threads.

Difficult to manage.

Easiest with context manager:

x = 0

x_lock = threading.Lock()

# Example critical section

with x_lock:

# statements using x

Only one lock per thread! (or risk mysterious deadlocks).

Or use RLock for code-based locking (locking function/method execution rather than data access).

Subprocesses (subprocess)¶

Subprocesses are completely separate processes invoked from a master process (your python program).

Usually used to call non-python programs (shell commands). But of course, a Python program can be a command line program as well, so you can call either your or other python programs this way.

Easy invocation:

import subprocess

subprocess.run('ls')

The program halts while waiting for the subprocess to finish. (unless you call it from a thread!)

You can control communication with the subprocess via:

stdout, stdin, stderr with:

subprocess.Popen

Lots of options there!