Asychronous Programming

Async: Not knowing what is happening when…

Asynchronous Programming

Another way to achieve concurrency

Approaches:

Event Loops

Callbacks

Coroutines

Why Async?

This is a pretty good overview of why you might want to use async:

https://hackernoon.com/asyncio-for-the-working-python-developer-5c468e6e2e8e#.dlhcuy23h

In: “A Web Crawler With asyncio Coroutines”, Guido himself writes:

Many networked programs spend their time not computing, but holding open many connections that are slow, or have infrequent events. These programs present a very different challenge: to wait for a huge number of network events efficiently. A contemporary approach to this problem is asynchronous I/O, or “async”.

http://www.aosabook.org/en/500L/a-web-crawler-with-asyncio-coroutines.html

My take:

Async is the good approach to support many connections that are spending a lot of time waiting, and doing short tasks when they do have something to do.

NOTE: the backbone of the web is HTTP – which is a “stateless” protocol. That is, each request is independent (state is “faked” with sessions via cookies). So “classic” web apps are NOT keeping many connections alive, there may be many clients at once, but each request is still independent. And often there is substantial work to be done with each one. A multi-threaded or multi-processes web server works fine for this.

Single Page Apps and WebSockets

“Single Page Apps”

A single-page application (SPA) is a web application … providing a user experience similar to that of a desktop application. … Interaction with the single page application often involves dynamic communication with the web server behind the scenes.

Communication with the web service can be regular old http (AJAX), or in modern implementations:

WebSocket:

WebSocket is a computer communications protocol, providing full-duplex communication channels over a single TCP connection.

WebSocket gives the advantage of “pushing” – the server can push information to the client, rather than the client having to poll the server to see if anything needs to be updated.

Either HTTP or WebSocket can generate many small requests to the server, which async is good for, but WebSocket pretty much requires an async server if you want it to scale well, as each active client is keeping a connection open.

Also: often a web service is depending on other web services to do its task. Kind of nice if your web server can do other things while waiting on a third-party service.

Client-side HTTP

Another nice use for async is client side HTTP:

When you make an http request, there is often a substantial lag time between making the request and getting the response.

The server receives the request, and it may have to do a fair bit of processing before it can return something – and it takes time for the response to travel over the wire.

With “regular” requests – the program is halted while it’s waiting for the server to do its thing. (“Blocking” – see below)

With async, the program can do other things while the request is waiting for the server to respond.

Blocking

A “Blocking” call means a function call that does not return until it is complete. That is, an ordinary old function call:

call_a_func()

The program will stop there and wait until the function returns before moving on. Nothing else can happen. Usually this is fine, the program may not be able to do anything else until it gets the result of that function anyway.

But what if:

That function will take a while?

And it’s mostly just waiting for the network or database, or….

Maybe your application needs to be responsive to user input, or you want it to do other work while that function is doing its thing. Especially if it’s mostly just waiting for a response to return. How do you deal with that?

Event Loops

Asynchronous programming is not new – it is the key component of traditional desktop Graphical User Interface Programs. The GUI version is often referred to as “event-driven” development:

You write “event handlers” that respond to particular events in the GUI: moving the mouse, clicking on a button, etc.

The trick is that you don’t know in what order anything might happen – there are multiple GUI objects on the screen at a given time, and users could click on any of them in any order.

This is all handled by an “event loop”, essentially code like this:

while True:

evt = event_queue.pop()

if evt:

evt.call_handler()

That’s it – it is an infinite loop that continually looks to see if there are any events to handle, and if there are, it calls the event handler for that event. Meanwhile, the system is putting events on the event queue as they occur: someone moving the mouse, typing in a control, etc.

It’s important that event handlers run quickly – if they take a long time to run, then the GUI is “locked up”, or not responsive to user input.

If the program does need to do some work that takes time, it needs to do that work in another thread or processes, and then put an event on the event queue when it is done.

For some examples of this, see:

Callbacks

Callbacks are a way to tell a non-blocking function what to do when they are done. This is a common way for systems to handle non-blocking operations. For instance, in Javascript, http requests are non-blocking. The request function call will return right away.

request('http://www.google.com',

function(error, response, body){

console.log(body);

});

What this means is:

Make a request to Google, and when the request is complete, call the function with three parameters: error, response, and body. This function is defined inline, and simply passes the body to the console log. But it could do anything.

That function is put on the event queue when the request is done, and will be called when the other events on the queue are processed.

Contrast with the “normal” python request library:

import requests

r = requests.get('http://www.google.com')

print(r.text)

The difference here is that the program will wait for requests.get() call to return, and that won’t happen until the request is complete. If you are making a lot of requests and they take a while, that is a lot of time sitting around waiting for the server when your computer isn’t doing anything.

Note that javascript began as a way to automate stuff on web pages – it lets you attach actions to various events in the browser: clicking button or what have you. The “callback” approach is natural for this. And once that structure was there, it made sense to keep it when making requests directly from code, that is doing: Asychronous Javascript and XML – i.e. AJAX. That’s why callback-based async is “built in” to Javascript.

Async programming usually (always?) involves an event loop to schedule operations.

But callbacks are only one way to communicate with the event loop.

Coroutines

Coroutines are computer program components that generalize subroutines for non-preemptive multitasking, by allowing multiple entry points for suspending and resuming execution at certain locations. Coroutines are well-suited for implementing more familiar program components such as cooperative tasks, exceptions, event loops, iterators, infinite lists and pipes.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coroutine

Coroutines are functions that can hold state, and varies between invocations; there can be multiple instances of a given coroutine at once.

This may sound a bit familiar from generators – a generator function can hold state when it yields, and there can be multiple instances of the same generator function at once.

In fact, you can use generators and yield to make coroutines, and that was done in Python before version 3.5 added new features to directly support coroutines.

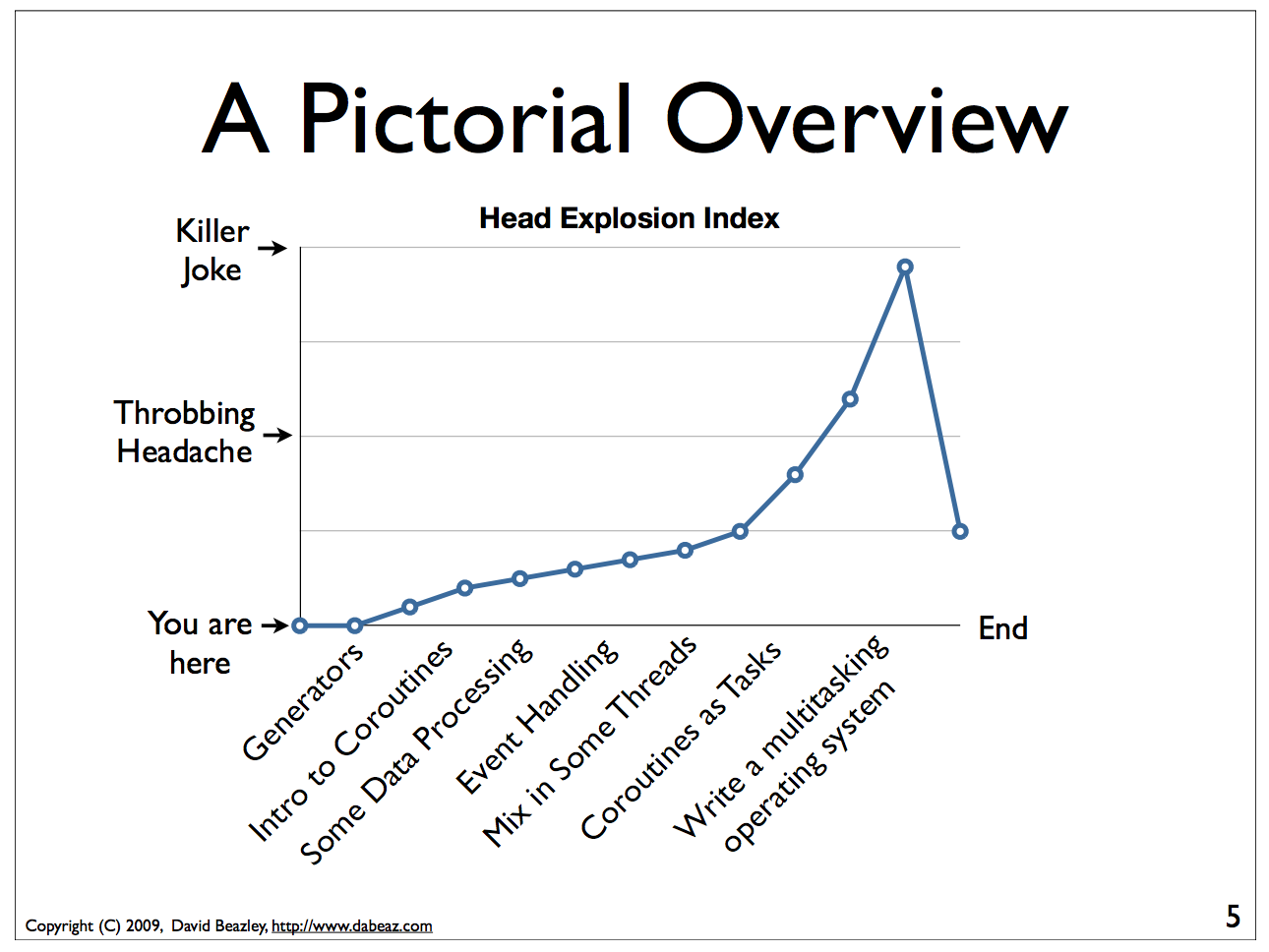

Warning: This is really hard stuff to wrap your head around!

(from: http://www.dabeaz.com/coroutines/Coroutines.pdf – which is a pretty good talk to read if you want to understand this stuff)

async / await

In Python 3.5, the async and await keywords were added to make coroutines “native” and more clear.

NOTE: async and await are still pretty new to Python. So if you look for tutorials, blog posts, etc. about asynchronous programming, they mostly either use or refer to the “old” way to do it (Including David Beazley’s talk above). In these notes, I am ONLY talking about the new way. I hope that’s less confusing. But it can be confusing to read older materials.

NOTE2: In addition to older documentation, the asyncio package in the standard library pre-dates async and await – so it supports the older style as well as the new style – another source of confusion.

The Trio project is worth a look for a cleaner API.

Using async/await

You define a coroutine with the async keyword:

async def ping_server(ip):

pass

When you call ping_server(), it doesn’t run the code. What it does is return a coroutine, all set up and ready to go.

In [12]: cr = ping_server(5)

In [13]: cr

Out[13]: <coroutine object ping_server at 0x104d75620>

Running a Coroutine

So how do you actually run the code in a coroutine?

await

await a_coroutine

It’s kind of like yield (from generators), but instead it returns the next value from the coroutine, and pauses execution so other things can run.

await suspends the execution (letting other code run) until the object called returns.

When you call await on an object, it needs to be an “awaitable” object: an object that defines an __await__() method which returns either an iterator which is not a coroutine itself, or a coroutine – which are considered awaitable objects.

Think of async/await as an API for asynchronous programming

async/await is really an API for asynchronous programming: People shouldn’t think that async/await as synonymous with asyncio, but instead think that asyncio is a framework that can utilize the async/await API for asynchronous programming. In fact, this view is supported by the fact that there are other async frameworks that use async/await – like the Trio package mentioned above.

Future objects

A Future object encapsulates the asynchronous execution of a callable – it “holds” the code to be run later.

It also contains methods like:

cancel():Cancel the future and schedule callbacks.

done():Return True if the future is done.

result():Return the result this future represents.

add_done_callback(fn):Add a callback to be run when the future becomes done.

set_result(result):Mark the future done and set its result.

A coroutine isn’t a future, but they can be wrapped in one by the event loop.

For the most part, you don’t need to work directly with futures.

NOTE: there is also the concurrent.futures module, which provides “future” objects that work with threads or processes, rather than an async event loop.

The Event Loop

The whole point of this to to pass events along to an event loop. So you can’t really do anything without one.

The asyncio package provides an event loop:

The asyncio event loop can do a lot:

Register, execute, and cancel delayed calls (asynchronous functions)

Create client and server transports for communication

Create subprocesses and transports for communication with another program

Delegate function calls to a pool of threads

But the simple option is to use it to run coroutines:

import asyncio

async def say_something():

print('This was run by the loop')

# getting an event loop

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

# run it:

loop.run_until_complete(say_something())

Note that asyncio.get_event_loop() will create an event loop in the main thread if one doesn’t exist – and return the existing loop if one does exist. So you can use it to get the already existing, and maybe running, loop from anywhere.

This is not a very interesting example – after all, the coroutine only does one thing and exits out, so the loop simply runs one event and is done.

Let’s make that a tiny bit more interesting with multiple events:

import asyncio

async def say_lots(num):

for i in range(num):

print('This was run by the loop:')

await asyncio.sleep(0.2)

# getting an event loop

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

# run it:

loop.run_until_complete(say_lots(5))

print("done with loop")

Still not very interesting – technically async, but with only one coroutine, not much to it.

NOTE: The event loop requires some setup, and it’s not very happy when you stop and try to restart it. So you may have issues if you run this kind of code from iPython – each time you run it, you’re still in the same Python process, so the event loop is whatever state it was left by the previous code. If you get any errors, simply restart iPython, or just run the scripts by themselves:

$ python ultra_simple.py

So let’s see an even more interesting example:

import asyncio

import time

import datetime

import random

# using "async" makes this a coroutine:

# its code can be run by the event loop

async def display_date(num):

end_time = time.time() + 10.0 # we want it to run for 10 seconds.

while True: # keep doing this until break

print("instance: {} Time: {}".format(num, datetime.datetime.now()))

if (time.time()) >= end_time:

print("instance: {} is all done".format(num))

break

# pause for a random amount of time

await asyncio.sleep(random.randint(0, 3))

def shutdown():

print("shutdown called")

# you can access the event loop this way:

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

loop.stop()

# You register "futures" on the loop this way:

asyncio.ensure_future(display_date(1))

asyncio.ensure_future(display_date(2))

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

# or add tasks to the loop like this:

loop.create_task(display_date(3))

loop.create_task(display_date(4))

# this will shut the event loop down in 15 seconds

loop.call_later(15, shutdown)

print("about to run loop")

# this is a blocking call

loop.run_forever()

print("loop exited")

Calling a regular function

The usual way to use the event loop is to schedule “awaitable” tasks – i.e. coroutines.

But sometimes you need to call a regular old function.

This is more like the traditional “callback” style:

You can do that with:

event_loop.call_soon(callback, *args)

This will put an event on the event loop, and call the function (callable) passed in, passing on any extra arguments as keyword arguments. It will run “soon”

Similarly, you can schedule a callable to be run some number of seconds in the future:

event_loop.call_later(delay, callback, *args)

Or at some specified time:

event_loop.call_at(when, callback, *args)

Absolute time corresponds to the event loop’s time() method: event_loop.time()

If you need to put an event on the loop from a separate thread, you can use:

event_loop.call_soon_threadsafe(callback, *args)

Giving up control

await passes control back to the event loop – cooperative multitasking!

Usually, you actually need to wait for a task of some sort. but if not, and you still need to give up control, you can use:

await asyncio.sleep(0)

You can, of course, pause for a period of time (greater than zero), but other than demos, I’m not sure why you’d want to do that.

Running Blocking Code

Sometimes you really do need to run “blocking” code – maybe a long computation, or reading a big file, or…..

In that case, if you don’t want your app locked up – you need to put it in a separate thread (or process). Use:

result = await loop.run_in_executor(Executor, function)

This will run the function in the specified Executor:

https://docs.python.org/3/library/concurrent.futures.html#concurrent.futures.Executor

If Executor is None – the default is used.

import asyncio

import time

import datetime

import random

async def small_task(num):

"""

Just something to give us little tasks that run at random intervals

These will go on forever

"""

while True: # keep doing this until break

print("task: {} run".format(num))

# pause for a random amount of time between 0 and 2 seconds

await asyncio.sleep(random.random() * 2)

async def slow_task():

while True: # keep going forever

print("running the slow task- blocking!")

# This will block for 2-10 seconds!

result = slow_function(random.random() * 8 + 2)

# uncomment to put it on a different thread:

# result = await loop.run_in_executor(None,

# slow_function,

# random.random() * 8 + 2)

print("slow function done: result", result)

await asyncio.sleep(0.1) # to release the loop

def slow_function(duration):

"""

this is a fake function that takes a long time, and blocks

"""

time.sleep(duration)

print("slow task complete")

return duration

# get a loop going:

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

# or add tasks to the loop like this:

loop.create_task(small_task(1))

loop.create_task(small_task(2))

loop.create_task(small_task(3))

loop.create_task(small_task(4))

# Add the slow one

loop.create_task(slow_task())

print("about to run loop")

# this is a blocking call

# we will need to hit ^C to stop it...

loop.run_forever()

print("loop exited")

Running a bunch of tasks

Sometimes you have a bunch of individual tasks to complete, but it does not matter in what order they are done.

asyncio.gather() collects a bunch of individual coroutines (or futures) together, runs them all (in parallel), and puts the results in a list.

Remember that they are now run in arbitrary order.

Doing real work with async

So what kinds of real things can you do with asynchronous programming?

asyncio provides the core tools to write asynchronous programs:

An event loop with a lot of features

Asynchronous versions of core network protocols: i.e. sockets.

file watching

…

But chances are, if you want to do something real, you’ll use a library..

Web servers and clients

There have been a few async frameworks around for Python for a while:

The granddaddy of them all:

Twisted https://twistedmatrix.com/trac/

Relative Newcomer:

Tornado: http://www.tornadoweb.org/en/stable/

Using the latest and greatest:

Once the asyncio package was added to the standard lib the tools are there to build “proper” http servers, etc:

aiohttp is an http server (and client) built on top of asyncio:

http://aiohttp.readthedocs.io/

(Twisted, Tornado, and the others have their own implementation of much of what is in asyncio, as they existed before asyncio existed)

As it’s the most “modern” implementation – we will use it for examples in the rest of this class:

aiohttp

Supports both Client and HTTP Server.

Supports both Server WebSockets and Client WebSockets out-of-the-box.

Web-server has Middlewares, Signals and pluggable routing.

Installing:

pip install aiohttp

An async client example:

If you need to make a lot of requests to collect data, or whatever, it’s likely your code is taking a lot of time to wait for the server to return. If it’s a slow server, it could be much more time waiting than doing real work.

This is where async shines!

This example borrowed from:

Asynchronous HTTP Requests in Python

It’s a really nice example.

The goal is to collect statistics for various NBA players. It turns out the NBA has an API for accessing statistics:

It’s kinda slow, but has a lot of great data – if you’re into that kind of thing.

Turns out that it’s a picky API – and I can’t get the async version to work – maybe the server gets upset when you hit it too hard?

Can you get it to work?

Synchronous version:

nba_stats_sync.py

And the Asynchronous version:

nba_stats_async.py

One that works:

Here is a similar example that works:

This is a “classic” regular old synchronous version:

and here is an async version

Let’s take a look.

TODO: Look at async example in multi-threading server example.

References:

The Asyncio Cheat Sheet: This is a pretty helpful, how to do it guide.

http://cheat.readthedocs.io/en/latest/python/asyncio.html

David Beazley: Concurrency from the ground up.

He writes a full async client server from scratch before your eyes – this guy can write code faster than most of us can read it…

David Beazley: asyncio:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lYe8W04ERnY

And David Beazley’s “Curio” package – an async package designed primarily for learning, rather than production use.