Threading and multiprocessing

Threading / multiprocessing

How to actually DO threading and multiprocessing:

threadingmodulemultiprocessingmodule

Parallel programming can be hard!

If your problem can be solved sequentially, consider the costs and benefits before going parallel.

Parallelization Strategy for Performance

Not every problem is parallelizable

There is an optimal number of threads for each problem in each environment, so make it tunable

Working concurrently opens up synchronization issues

Methods for synchronizing threads:

locks

queues

signaling/messaging mechanisms

The mechanics: how do you use threads and/or processes

Python provides the threading and multiprocessing modules to facility concurrency.

They have similar APIs – so you can use them in similar ways.

Key points:

There is no Python thread scheduler, it is up to the host OS. yes these are “true” threads.

Works well for I/O bound problems, can use literally thousands of threads

Limit CPU-bound processing to C extensions (that release the GIL)

Do not use for CPU bound problems, will go slower than no threads, especially on multiple cores!!! (see David Beazley’s talk referenced above)

Starting threads is relatively simple, but there are many potential issues.

We already talked about shared data, this can lead to a “race condition”.

May produce slightly different results every run

May just flake out mysteriously every once in a while

May run fine when testing, but fail when run on: - a slower system - a heavily loaded system - a larger dataset

Thus you must synchronize threads!

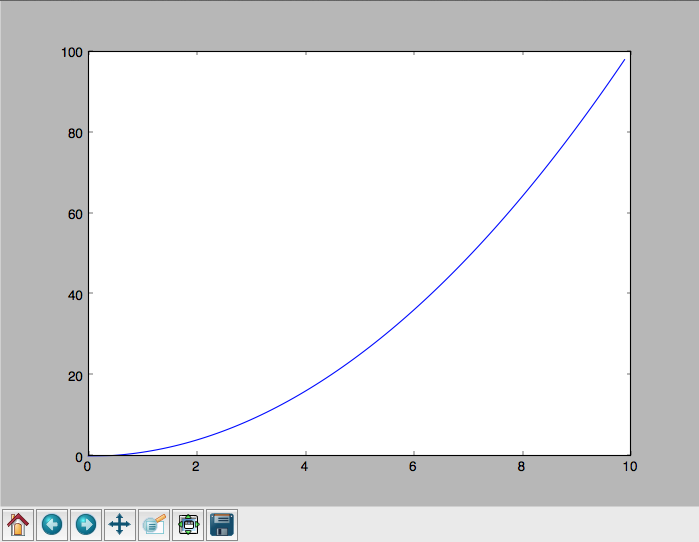

Example: A CPU bound problem

Numerically integrate the function \(y =x^2\) from 0 to 10.

http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=x%5E2

Parallel execution example

Consider the following code in:

integrate.py

def f(x):

return x**2

def integrate(f, a, b, N):

s = 0

dx = (b-a)/N

for i in xrange(N):

s += f(a+i*dx)

return s * dx

We can do better than this

Break down the problem into parallelizable chunks, then add the results together:

The threading module

Starting threads doesn’t take much:

import sys

import threading

import time

def func():

for i in xrange(5):

print("hello from thread %s" % threading.current_thread().name)

time.sleep(1)

threads = []

for i in xrange(3):

thread = threading.Thread(target=func, args=())

thread.start()

threads.append(thread)

The process will exit when the last non-daemon thread exits.

A thread can be specified as a daemon thread by setting its daemon attribute:

thread.daemon = Truedaemon threads get cut off at program exit, without any opportunity for cleanup. But you don’t have to track and manage them. Useful for things like garbage collection, network keepalives, ..

You can block and wait for a thread to exit with thread.join()

Subclassing Thread

You can add threading capability to your own classes

Subclass Thread and implement the run method

import threading

class MyThread(threading.Thread):

def run(self):

print("hello from %s" % threading.current_thread().name)

thread = MyThread()

thread.start()

Race Conditions

In the last example we saw threads competing for access to stdout.

Worse, if competing threads try to update the same value, we might get an unexpected race condition

Race conditions occur when multiple statements need to execute atomically, but get interrupted midway

No race condition

Thread 1 |

Thread 2 |

Integer value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

|||

read value |

← |

0 |

|

increase value |

0 |

||

write back |

→ |

1 |

|

read value |

← |

1 |

|

increase value |

1 |

||

write back |

→ |

2 |

Race Condition!

Thread 1 |

Thread 2 |

Integer value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

|||

read value |

← |

0 |

|

read value |

← |

0 |

|

increase value |

0 |

||

increase value |

0 |

||

write back |

→ |

1 |

|

write back |

→ |

1 |

Deadlocks

Synchronization and Critical Sections are used to control race conditions

But they introduce other potential problems…

like: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deadlock

“A deadlock is a situation in which two or more competing actions are each waiting for the other to finish, and thus neither ever does.”

When two trains approach each other at a crossing, both shall come to a full stop and neither shall start up again until the other has gone

See also Livelock:

Two people meet in a narrow corridor, and each tries to be polite by moving aside to let the other pass, but they end up swaying from side to side without making any progress because they both repeatedly move the same way at the same time.

Locks

Lock objects allow threads to control access to a resource until they’re done with it

This is known as mutual exclusion, often called “mutex”.

A Lock has two states: locked and unlocked

If multiple threads have access to the same Lock, they can police

themselves by calling its .acquire() and .release() methods

If a Lock is locked, .acquire will block until it becomes unlocked

These threads will wait in line politely for access to the statements in f()

Mutex locks (threading.Lock)

Probably most common

Only one thread can modify shared data at any given time

Thread determines when unlocked

Must put lock/unlock around critical code in ALL threads

Difficult to manage

Easiest with context manager:

x = 0

x_lock = threading.Lock()

# Example critical section

with x_lock:

# statements using x

Only one lock per thread! (or risk mysterious deadlocks)

Or use RLock for code-based locking (locking function/method execution rather than data access)

import threading

import time

lock = threading.Lock()

def f():

lock.acquire()

print("%s got lock" % threading.current_thread().name)

time.sleep(1)

lock.release()

threading.Thread(target=f).start()

threading.Thread(target=f).start()

threading.Thread(target=f).start()

Nonblocking Locking

.acquire() will return True if it successfully acquires a lock

Its first argument is a boolean which specifies whether a lock should

block or not. The default is True

import threading

lock = threading.Lock()

lock.acquire()

if not lock.acquire(False):

print("couldn't get lock")

lock.release()

if lock.acquire(False):

print("got lock")

threading.RLock - Reentrant Lock

Useful for recursive algorithms, a thread-specific count of the locks is maintained

A reentrant lock can be acquired multiple times by the same thread

Lock.release() must be called the same number of times as Lock.acquire()

by that thread

threading.Semaphore

Like an RLock, but in reverse

A Semaphore is given an initial counter value, defaulting to 1

Each call to acquire() decrements the counter, release() increments it

If acquire() is called on a Semaphore with a counter of 0, it will block

until the Semaphore counter is greater than 0.

Useful for controlling the maximum number of threads allowed to access a resource simultaneously

Events (threading.Event)

Threads can wait for particular event

Setting an event unblocks all waiting threads

Common use: barriers, notification

Condition (threading.Condition)

Combination of locking/signaling

lock protects code that establishes a “condition” (e.g., data available)

signal notifies threads that “condition” has changed

Common use: producer/consumer patterns

Locking Exercise

In: lock/stdout_writer.py

Multiple threads in the script write to stdout, and their output gets jumbled

Add a locking mechanism to give each thread exclusive access to stdout

Try adding a Semaphore to allow 2 threads access at once

Managing thread results

We need a thread safe way of storing results from multiple threads of execution. That is provided by the Queue module.

Queues allow multiple producers and multiple consumers to exchange data safely

Size of the queue is managed with the maxsize kwarg

It will block consumers if empty and block producers if full

If maxsize is less than or equal to zero, the queue size is infinite

from Queue import Queue

q = Queue(maxsize=10)

q.put(37337)

block = True

timeout = 2

print(q.get(block, timeout))

Queues (queue)

Easier to use than many of above

Do not need locks

Has signaling

Common use: producer/consumer patterns

from Queue import Queue

data_q = Queue()

Producer thread:

for item in produce_items():

data_q.put(item)

Consumer thread:

while True:

item = q.get()

consume_item(item)

Scheduling (sched)

Schedules based on time, either absolute or delay

Low level, so has many of the traps of the threading synchronization primitives.

Timed events (threading.timer)

Run a function at some time in the future:

import threading

def called_once():

"""

this function is designed to be called once in the future

"""

print("I just got called! It's now: {}".format(time.asctime()))

# setting it up to be called

t = Timer(interval=3, function=called_once)

t.start()

# you can cancel it if you want:

t.cancel()

Other Queue types

Queue.LifoQueue

Last In, First Out

Queue.PriorityQueue

Lowest valued entries are retrieved first

One pattern for PriorityQueue is to insert entries of form data by

inserting the tuple:

(priority_number, data)

Threading example with a queue

#!/usr/bin/env python

import threading

import queue

# from integrate.integrate import integrate, f

from integrate import f, integrate_numpy as integrate

from decorators import timer

@timer

def threading_integrate(f, a, b, N, thread_count=2):

"""break work into N chunks"""

N_chunk = int(float(N) / thread_count)

dx = float(b - a) / thread_count

results = queue.Queue()

def worker(*args):

results.put(integrate(*args))

for i in range(thread_count):

x0 = dx * i

x1 = x0 + dx

thread = threading.Thread(target=worker, args=(f, x0, x1, N_chunk))

thread.start()

print("Thread %s started" % thread.name)

return sum((results.get() for i in range(thread_count)))

if __name__ == "__main__":

# parameters of the integration

a = 0.0

b = 10.0

N = 10**8

thread_count = 8

print("Numerical solution with N=%(N)d : %(x)f" %

{'N': N, 'x': threading_integrate(f, a, b, N, thread_count=thread_count)})

Threading on a CPU bound problem

Try running the code in integrate_threads.py

It has a couple of tunable parameters:

a = 0.0 # the start of the integration

b = 10.0 # the end point of the integration

N = 10**8 # the number of steps to use in the integration

thread_count = 8 # the number of threads to use

What happens when you change the thread count? What thread count gives the maximum speed?

Multiprocessing

processes are completely isolated

no locking :) (and no GIL!)

instead of locking: messaging

multiprocessing provides an API very similar to threading, so the transition is easy

use multiprocessing.Process instead of threading.Thread

import multiprocessing

import os

import time

def func():

print "hello from process %s" % os.getpid()

time.sleep(1)

proc = multiprocessing.Process(target=func, args=())

proc.start()

proc = multiprocessing.Process(target=func, args=())

proc.start()

Differences with Threading

Multiprocessing has its own multiprocessing.Queue which handles

interprocess communication

Also has its own versions of Lock, RLock, Semaphore

from multiprocessing import Queue, Lock

multiprocessing.Pipe for 2-way process communication:

from multiprocessing import Pipe

parent_conn, child_conn = Pipe()

child_conn.send("foo")

print parent_conn.recv()

Messaging

Pipes (multiprocessing.Pipe)

Returns a pair of connected objects

Largely mimics Unix pipes, but higher level

send pickled objects or buffers

Queues (multiprocessing.Queue)

same interface as

queue.Queueimplemented on top of pipes

means you can pretty easily port threaded programs using queues to multiprocessing - queue is the only shared data - data is all pickled and unpickled to pass between processes – significant overhead.

Other features of the multiprocessing package

Pools

Shared objects and arrays

Synchronization primitives

Managed objects

Connections

Pooling

A processing pool contains worker processes with only a configured number running at one time

from multiprocessing import Pool

pool = Pool(processes=4)

The Pool module has several methods for adding jobs to the pool

apply_async(func[, args[, kwargs[, callback]]])

map_async(func, iterable[, chunksize[, callback]])

Pooling example

from multiprocessing import Pool

def f(x):

return x*x

if __name__ == '__main__':

pool = Pool(processes=4)

result = pool.apply_async(f, (10,))

print(result.get(timeout=1))

print(pool.map(f, range(10)))

it = pool.imap(f, range(10))

print(it.next())

print(it.next())

print(it.next(timeout=1))

import time

result = pool.apply_async(time.sleep, (10,))

print(result.get(timeout=1))

http://docs.python.org/3/library/multiprocessing.html#module-multiprocessing.pool

ThreadPool

Threading also has a pool

Confusingly, it lives in the multiprocessing module

from multiprocessing.pool import ThreadPool

pool = ThreadPool(processes=4)