Concurrent Programming

What does it mean to do something “Concurrently” ? It means multiple things are happening at the same time. But what are those “things”?

Parallelism is about processing multiple things at the same time – true parallelism requires multiple processors (or cores).

Concurrency is about handling multiple things at the same time – which may or may not be actually running in the processor at the same time (like network requests for instance).

Parallelism needs concurrency, but concurrency need not be in parallel.

Whirlwind Tour of Concurrency

Concurrency:

Having different code running at the same time, or kind of the same time.

Asynchrony:

The occurrence of events independent of the main program flow and ways to deal with such events.

Asynchrony and Concurrency are really two different things – you can do either one without the other – but they are closely related, and often used together. They solve different problems, but the problems and the solutions overlap.

“Concurrency is not parallelism” – Rob Pike: https://vimeo.com/49718712

Despite Rob Pike using an example about burning books, I recommend listening to at least the first half of his talk.

In that talk Rob Pike makes a key point: Breaking down tasks into concurrent subtasks only allows parallelism, it’s the scheduling of these subtasks that creates it.

And, indeed, once you have a set of subtasks, they can be scheduled in a truly parallel fashion, or managed asynchronously in a single thread (concurrent, but not parallel)

Types of Concurrency

Multithreading:

Multiple code paths sharing memory – one Python interpreter, one set of Python objects.

Multiprocessing:

Multiple code paths with separate memory space – completely separate Python interpreter.

Asyncronous programming:

Multiple “jobs” run at “arbitrary” times – but usually in one thread – i.e. only one code path, one interpreter.

Lots of different packages for both in the standard library and 3rd party libraries.

How to know what to choose?

IO bound vs. CPU bound – CPU bound requires multiprocessing (at least with pure Python)

Event driven cooperative multitasking vs. preemptive multitasking

Callbacks vs coroutines + scheduler/event loop

Motivations for parallel execution

Performance - Limited by “Amdahl’s Law”: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amdahl%27s_law

CPUs aren’t getting much faster

Event handling - If a system handles asynchronous events, a separate thread of execution could handle those events and let other threads do other work

- Examples:

Network applications

User interfaces

Parallel programming can be hard!

If your problem can be solved sequentially, consider the costs and benefits before going parallel.

Parallelization Strategy for Performance

Not every problem is parallelizable

There is an optimal number of threads for each problem in each environment, so make it tunable

Working concurrently opens up synchronization issues

Methods for synchronizing threads:

locks

queues

signaling/messaging mechanisms

Other options

Traditionally, concurency has been achieved through multiple process communication and in-process threads, as we’ve seen.

Another strategy is through micro-threads, implemented via coroutines and a scheduler.

A coroutine is a generalization of a subroutine which allows multiple entry points for suspending and resuming execution.

The threading and the multiprocessing modules follow a preemptive multitasking model

Coroutine based solutions follow a cooperative multitasking model:

Threads versus processes in Python

Threads are lightweight processes, run in the address space of an OS process, true OS level threads.

Therefore, a component of a process.

This allows multiple threads access to data in the same scope.

Threads can not gain the performance advantage of multiple processors due to the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)

But the GIL is released during IO, allowing IO bound processes to benefit from threading

Processes

A process contains all the instructions and data required to execute independently, so processes do not share data!

Mulitple processes best to speed up CPU bound operations.

The Python interpreter isn’t lightweight!

Communication between processes can be achieved via:

multiprocessing.Queue

multiprocessing.Pipe

and regular IPC (inter-process communication)

Data moved between processes must be pickleable

Advantages / Disadvantages of Threads

Advantages:

They share memory space:

Threads are relatively lightweight – shared memory means they can be created fairly quickly without much memory use.

Easy and cheap to pass data around (you are only passing a reference).

Disadvantages:

They share memory space:

Each thread is working with the same python objects.

Operations often take several steps and may be interrupted mid-stream

Thus, access to shared data is also non-deterministic

(race conditions)

Creating threads is easy, but programming with threads is difficult.

Q: Why did the multithreaded chicken cross the road?

A: to To other side. get the

—Jason Whittington

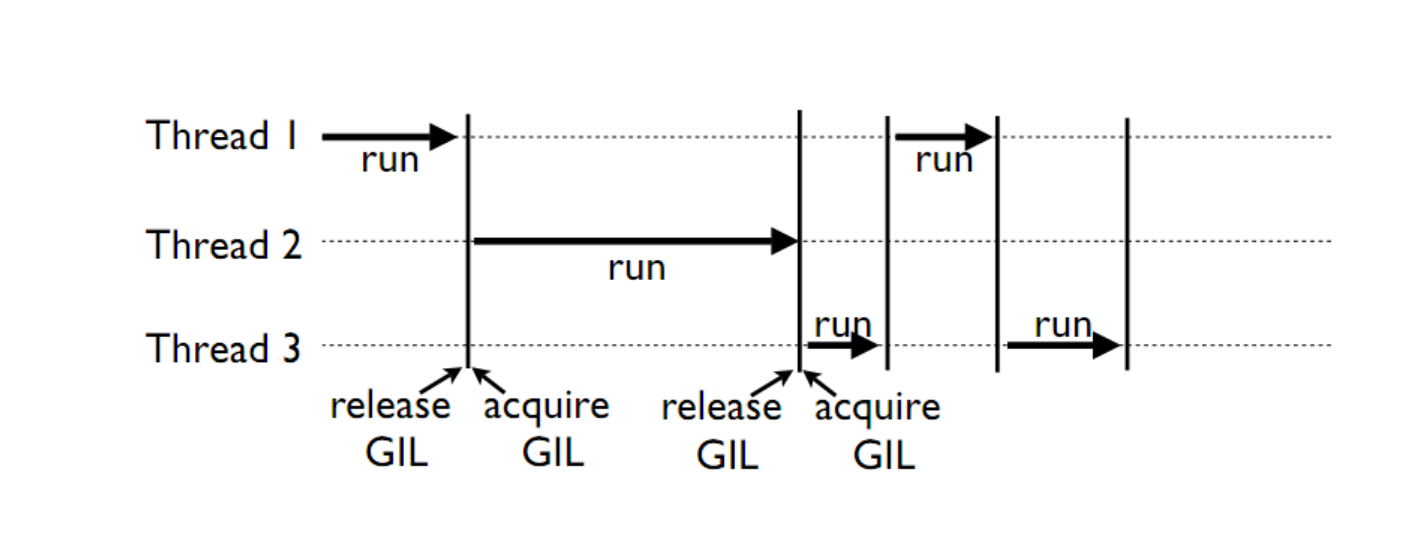

GIL

Global Interpreter Lock

(GIL)

This is a lock which must be obtained by each thread before it can execute, ensuring thread safety

The GIL is released during IO operations, so threads which spend time waiting on network or disk access can enjoy performance gains

The GIL is not unlike multitasking in humans, some things can truly be done in parallel, others have to be done by time slicing.

Note that potentially blocking or long-running operations, such as I/O, image processing, and NumPy number crunching, happen outside the GIL. Therefore it is only in multithreaded programs that spend a lot of time inside the GIL, interpreting CPython bytecode, that the GIL becomes a bottleneck. But: it can still cause performance degradation.

Not only will threads not help cpu-bound problems, but it can actually make things worse, especially on multi-core machines!

Python threads do not work well for computationally intensive work.

Python threads work well if the threads are spending time waiting for something:

Database Access

Network Access

File I/O

Some alternative Python implementations such as Jython and IronPython have no GIL

cPython and PyPy have one

More about the gil

More on the GIL:

https://emptysqua.re/blog/grok-the-gil-fast-thread-safe-python/

If you really want to understand the GIL – and get blown away – watch this one:

http://pyvideo.org/pycon-us-2010/pycon-2010–understanding-the-python-gil—82.html

NOTE: The GIL seems like such an obvious limitation that you’ve got to wonder why it’s there. And there have been multiple efforts to remove it. But it turns out that Python’s design makes that very hard (impossible?) without severely reducing performance on single threaded programs.

The current “Best” effort is Larry Hastings’ gilectomy

But that may be stalled out at this point, too. No one should count on it going away in cPython.

But: Personal Opinion: Python is not really (directly) suited to the kind of computationally intensive work that the GIL really hampers. And extension modules (i.e. numpy) can release the GIL!

Posted without comment

Advantages / Disadvantages of Processes

Processes are heavier weight – each process makes a copy of the entire interpreter (Mostly…) – uses more resources.

You need to copy the data you need back and forth between processes.

Slower to start, slower to use, more memory.

But as the entire python process is copied, each subprocess is working with the different objects – they can’t step on each other. So there is:

no GIL

Multiprocessing is suitable for computationally intensive work.

Works best for “large” problems with not much data to pass back and forth, as that’s what’s expensive.

Note that there are ways to share memory between processes, if you have a lot of read-only data that needs to be used. (see Memory Maps)

Synchronization options:

Locks (Mutex: mutual exclusion, Rlock: reentrant lock)

Semaphore

BoundedSemaphore

Event

Condition

Queues

Mutex locks (threading.Lock)

Probably most common

Only one thread can modify shared data at any given time

Thread determines when unlocked

Must put lock/unlock around critical code in ALL threads

Difficult to manage

Easiest with context manager:

x = 0

x_lock = threading.Lock()

# Example critical section

with x_lock:

# statements using x

Only one lock per thread! (or risk mysterious deadlocks)

Or use RLock for code-based locking (locking function/method execution rather than data access)

Subprocesses (subprocess)

Subprocesses are completely separate processes invoked from a master process (your python program).

Usually used to call non-python programs (shell commands). But of course, a Python program can be a command line program as well, so you can call either your or other python programs this way.

Easy invocation:

import subprocess

subprocess.run('ls')

The program halts while waiting for the subprocess to finish. (unless you call it from a thread!)

You can control communication with the subprocess via:

stdout, stdin, stderr with:

subprocess.Popen

Lots of options there!

Pipes and pickle and subprocess

Very low level, for the brave of heart

Can send just about any Python object

For this to work, you need to send messages, as each process runs its own independent Python interpreter.

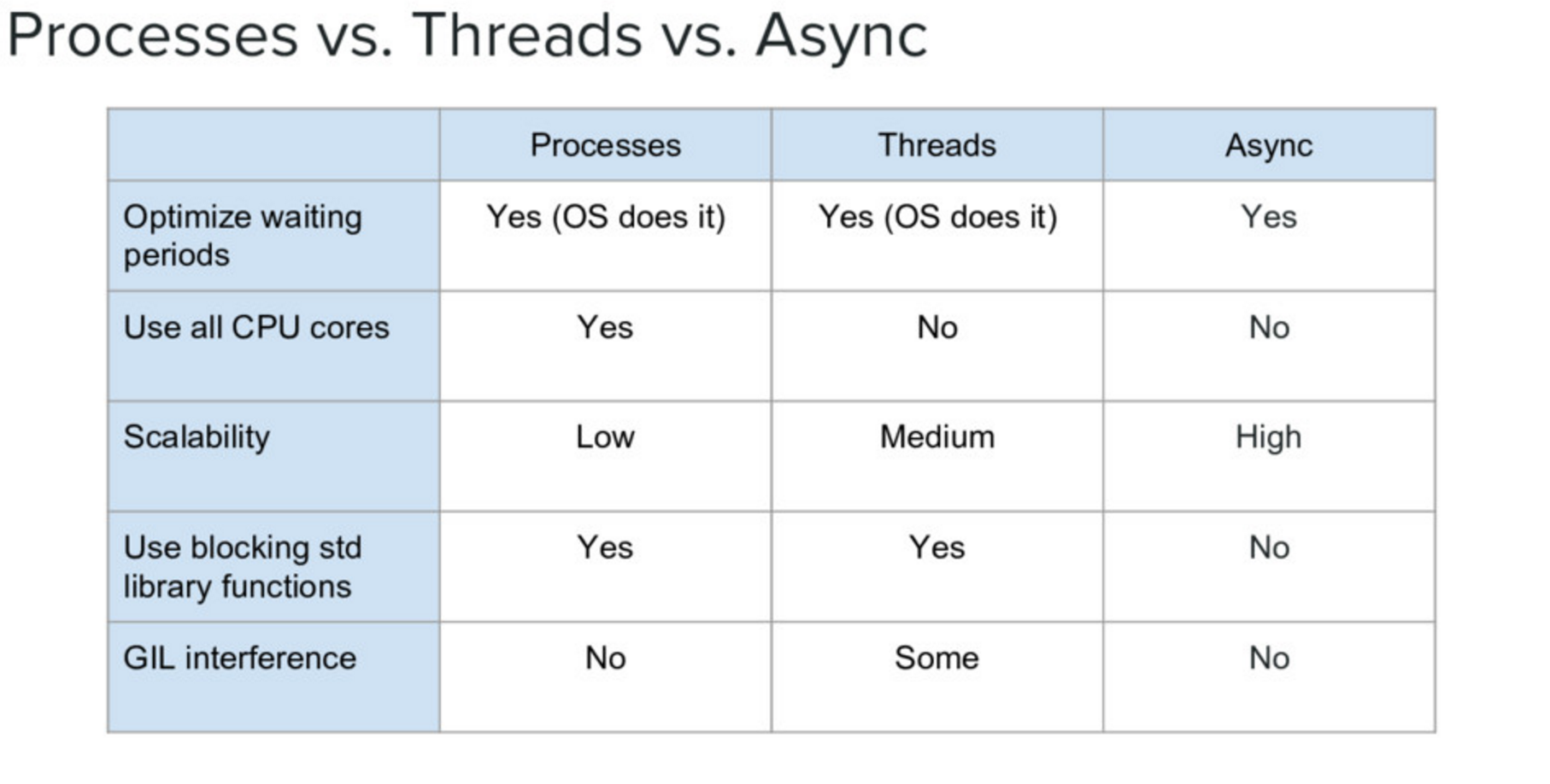

When to Use What